TransAlta's Sundance Power Plant

Source: Financial Post c/o TransAlta

What will it cost to

retire coal early in Alberta?

There seems to be no shortage of opinion pieces seeking to address

this question in papers ranging from the Calgary Herald to the Financial Post.

One such article, “

Get ready Albertans, you’re about to pay a steep bill to kill coal,”

echoes the concerns of many Albertans I know and I want to explore these

concerns more fully and quantitatively than most of the articles I have seen to

date. For those just looking for the answer to how much I estimate it will cost

to retire coal early in Alberta, feel free to skip to the conclusion below.

Caveat/Fine print: my analysis does not model the complex realities of the deregulated, multi-actor bidding system that is the Alberta electricity system. Instead, it relies on a simpler analysis involving levelized costs of energy over the lifetime of power plants, which should, in theory be recovered in the long-run. That being said, it has its limitations. Also, I also do not weigh in on the potential lawsuits from coal-fired power plant owners which may result from the early retirement of their facilities. These lawsuits could have a large impact on the final cost of coal retirement.

Alberta’s grid was not necessarily on track to be just 10% coal by 2034

Many

authors have been claiming that Alberta's grid will be 10% coal-fired

by 2034, and while this claim has some merit, it is also misleading. The

authors use what is referred to as power plant capacity when deriving

their

numbers. This means the maximum potential of a particular power plant to

produce

energy in a given time-period. The problem with this is that it doesn’t

show

how often the different power plants are being used. For example, in

2014, coal

made up 41% of the power capacity in the province, but produced 55% of

our

energy. Wind on the other hand, made up 10% of the capacity, but

produced 4% of

our total energy (Source: Alberta Utilities Commission). As you can see

in the graph below, capacity doesn’t

show how much each fuel is contributing to energy production in the

province.

Coal-fired power plants also make up an overwhelming

percentage of carbon and other air emissions (mercury, sulfur dioxide, etc.)

from electricity production. In 2011, coal made up 55% of the MWh produced, but

accounted for 91% of the carbon emissions from the electricity sector (Source:

Alberta Utilities Commission and the Federal National Pollutant Release Inventory).

Ontario’s electricity prices have not increased by 80% due to coal being retired in the

province

It is unwise to compare the Alberta and Ontario electricity

markets for a number of reasons. To understand why, we need to look at how each

of these provinces deregulated their energy sectors.

What the hell is

deregulation?

Deregulation refers to how a province changes from the

government signing individual contracts with power plants for electricity to a

centralized market where power plants bid their production every half-hour or

hour.

Why does it matter how

you go from one to the other?

Regulated markets are managed by the government or central

utility, which pays a set price for electricity over the life of the power

plants. In order for the market mentioned above to function properly, these

contracts must be “transitioned” to the market. That is, these power plants

must be paid out for the value of the contracts, or that value must be

accounted for in the new system.

So how did Alberta

deal with these contracts?

Alberta managed these contracts by auctioning off the rights

of the power to another party through a government agency called the Balancing Pool. For example, TransCanada bought the Power Purchase Agreement for the Sheerness Power Station for 20 years for $585 million. Through this, the government was

able to cover the cost of the pre-existing contracts, and the company that

bought the rights to the power plant could bid the plant into the market as it

saw fit. Many of the corporations who owned these contracts have stepped away

from them since NDP passed their new carbon regulations and the impact of this

is a major uncertainty. For more information on Alberta's deregulation, see the

AESO's Deregulation Report)

|

| According to the Auditor General's report in December 2015, Ontario overpaid for much of its renewable energy capacity. |

How did Ontario do it?

Ontario developed something called the

Global

Adjustment, a cost that fluctuates based on the average price of the market

to make sure that power plants recovered the revenue that they were guaranteed

through the existing contracts. This eliminates the ability for the market to

drive cost-savings as any decrease in the market price for electricity is later

accounted for by an increase in the global adjustment.

Why have Ontario’s

power prices increased so much in the past decade?

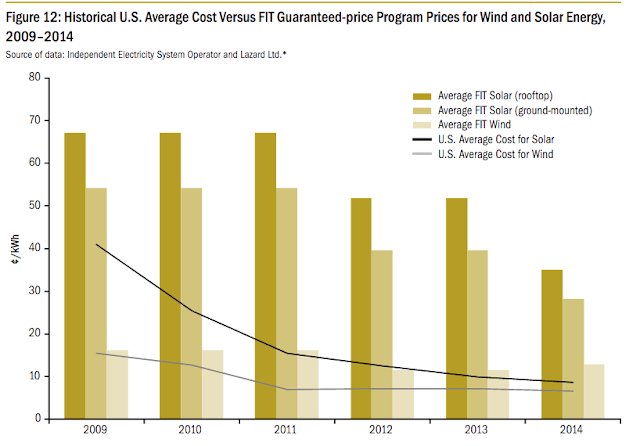

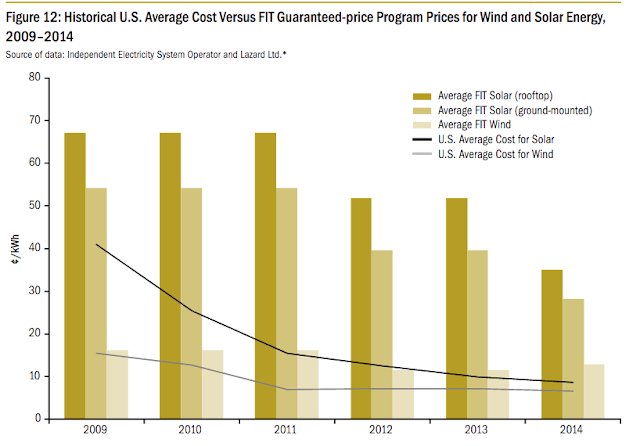

Ontario’s power prices have increased due to a number of

policies introduced in the past decade. This includes a Feed-in Tariff program,

which has been widely criticized for inefficiently and artificially

establishing rates paid to renewable generators.

According to the Ontario auditor general, the renewable

energy contracts signed through this and other programs is responsible for $9.2

billion or about 33% of the increase in Ontario’s power prices. Alternatively,

early coal retirement is more difficult to obtain numbers for. However, based

on 2010 filing with the Ontario government, OPG had liabilities relating to

Power Purchase Agreements of around $2.2 billion, some of which would have been

regarding the Nanticoke and Lambton coal-fired power plants, the two largest by far

of the four coal plants that were retired in Ontario. We could conclude from this that coal

retirement is therefore not the main culprit in the rise of Ontario’s power

prices.

The unanswered question: What will happen to Alberta energy costs because of

coal?

To understand the cost of retiring coal early, you can’t

simply look at the cost of building new power plants, because consumers in

Alberta are not charged based on this capital cost. Instead, you have to

compare the marginal cost of each power plant type with the inclusion of the

increased carbon tax. In addition, you also have to factor in when those power

plants would have been built anyway and then count only the additional cost for

the additional years. Coal power plants in the province will be retired on the

schedule below as a result of rules established by the Harper administration:

The bulk of the coal-fired power plants will be

offline by 2034. This means that the increase to our power bills is the

increase in cost to the dispatched energy from the 2.5 GW of coal that would

have remained online.

The cost to retire coal early

With this in mind we can use the average Alberta grid price,

the cost per MWh of new natural gas generation, and the differences in carbon

content of the coal-fired and natural gas-fired generation to build a model

estimating the increased costs to the energy system in Alberta because of early

coal retirements.

The increase in costs would be around $7.5 Billion on 80TWh of energy per year, or

$3.34/MWh. This would result in an increase of about 10% to Alberta wholesale

energy prices. For consumers, wholesale energy prices make up around 37% of

your energy bill. So the cost to the average household is about

$1.10 per month. This will result in a reduction of carbon emissions by almost 95 million tonnes, almost the annual emissions of the entire Albertan oil sands and it will dramatically lower the mercury and sulfur dioxide emissions in the province (

human impacts of Mercury and Sulfur Dioxide in the Atmosphere).

|

| According to Energy Alberta, more than 10,000 people are employed by the coal industry in Alberta |

Thirteen dollars per year per Albertan household hardly seems to be the economic doomsday that many project, but some people are saying that the slow addition of small expenses such as this may eventually break the back of the Albertan economy, and this must be part of the analysis. What is the impact of all additional costs associated with NDP programs and how do we make sure that not only are these costs worthwhile, but also affordable? Last, when the coal plants close, the communities that have benefited from these jobs for decades will face economic difficulties.

The NDP must put forward a plan for the economic transition of these communities and the entire province should push them for it.

For those interested

in a much more in-depth analysis, take a look at Genalta’s paper. Note: this paper was written before the fall of oil prices and as a result, reflects the power prices of that time.

Sources

National Pollutant Release

Inventory: